Programs - Special Screening

Yes

11/21(Fri)14:45 -Asahi Hall

11/26(Wed)15:55 -Human Trust Cinema Yurakucho

France, Israel, Cyprus, Germany / 2025 / 150min

Director:Nadav Lapid

After the 2023 October 7th incident in Israel, a struggling musician Y takes an offer to compose a new patriotic song that screams for the annihilation of Gaza and stands obviously pro-war to pay his bills. Y is tormented by anguish of conscience as an artist and as a citizen, while his dancer wife, Jasmine, also begins to feel doubts and emotional distance from him.

A provocative drama full of anger, where fierce political satire and deep sadness coexist, the film is a poignant portrayal of the collective mentality of Israeli society after October 7th. Diverging from a conventional narrative framework, it is structured as if a powerful emotional turbulence were burned directly onto the screen. A struggling musician, Y, lives in the frenzy of Tel Aviv's party culture with his dancer wife. The story unfolds when Y is offered to compose a new patriotic song inciting retaliation against Gaza. A painful self-condemnation begins when Y is torn between his country and his artistic conscience. Following “Synonyms” (2019) and “Ahed’s Knee” (2021), the film questions national identity with unprecedented ferocity and magnifies the moral and emotional struggle that the world faces as a soul-destroying personal testimony. The film world premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival.

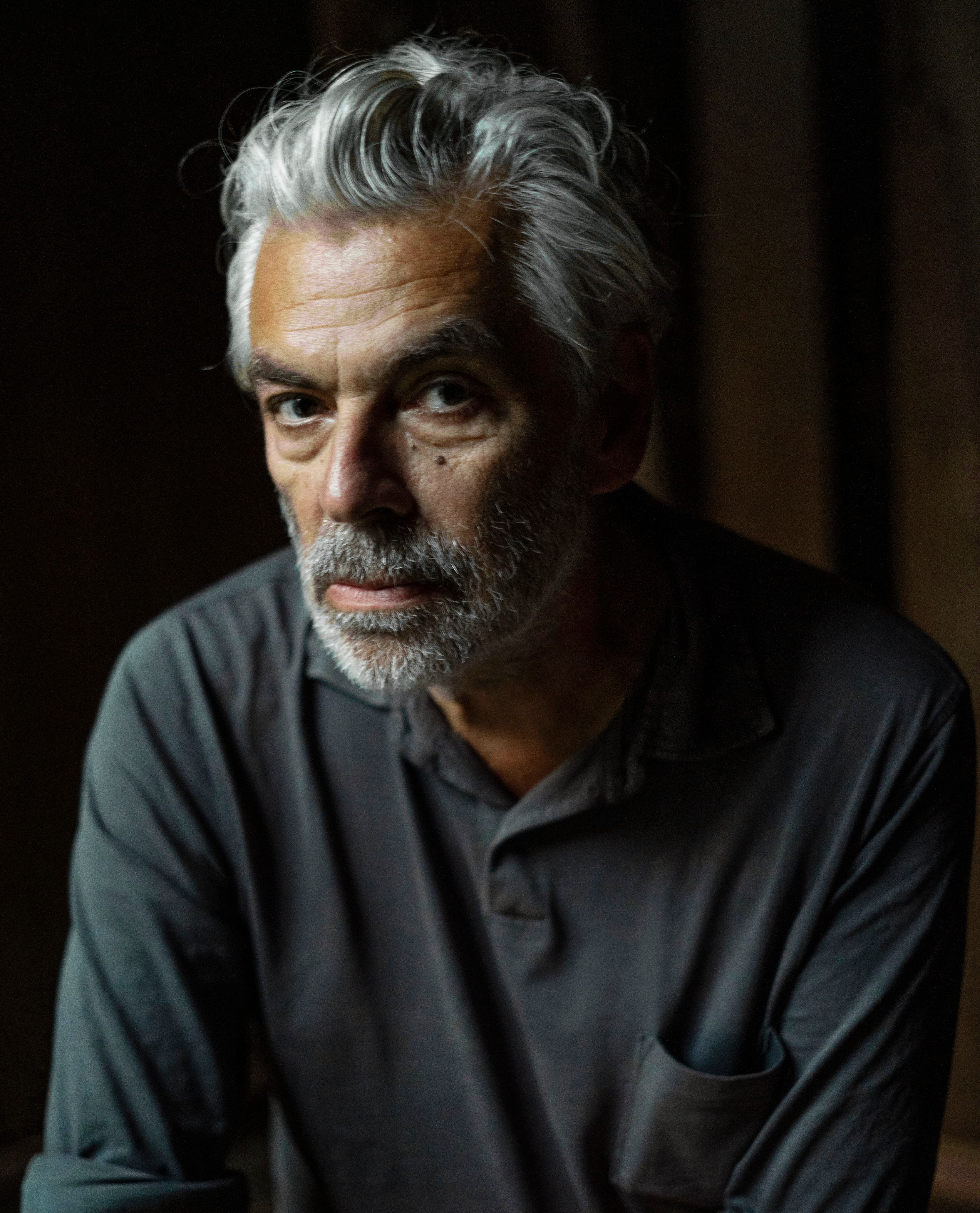

Director:Nadav Lapid

Born in Tel Aviv in 1975, currently living in Paris, he is one of Israel’s most distinctive filmmakers. His debut feature “Policeman” (2011) won the Special Jury Prize at Locarno Film Festival. His third film, “Synonyms” (2019), received the Golden Bear at the Berlinale, followed by “Ahed’s Knee” (2021), which won the Jury Prize at Cannes Film Festival and was screened at TOKYO FILMeX 2021. In 2023, he joined fellow filmmakers worldwide in signing an open letter calling for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza.

Director’s statement

On the title and theme

What I am talking about in the movie goes way beyond the situation in Israel. I found that approaching the subject from the no perspective was somehow old-fashioned. The best way to speak of the power that prevails in the world is by being crushed by it. You bump up against the limits of the ant yelling at an elephant. Submission is currently the only truth. At one point in the film, Y. tells his son, “Give up as early as possible. Submission is happiness.” My characters have widely explored the field of rage, protest and revolt. Here, it’s the opposite. In my previous movies, there was the fantasy that, thanks to the poems of a child or the cries of a man, the gulf that exists between the world we inhabit and the world we should inhabit would be reduced or flattened. I wanted to believe it, even if I knew I would be disappointed. I always felt close to characters who banged into walls or closed doors. I am still obsessed by those doors, open or closed, but banging my head against them is over for me. It’s become archaic. The way for me to talk about it today is to show someone who crawls to slip through the open door before it closes. I think that says more about the truth of the world, the truth of the artist in the moment. Y. is my first passive lead character, in the sense that he accepts everything, gives himself unconditionally. It becomes very stimulating on a cinematic level. In his movements and gestures, he is as active as he can be. He never stops moving or dancing. But his willpower and desire have been sterilized.

On the impact of the Gaza situation (October 7 attacks)

I was in Paris on October 7, and I was shocked, like many people, by what was happening in Israel. Beyond the event, since I’m a filmmaker, I wondered, after a few hours, what point there might be in making movies now, especially the one I was preparing about the condition of the artist. It took a dozen days before I prudently began to reopen my computer and scrutinize the screenplay. The first line of the screenplay is still in the movie. It comes from the mouth of the chief of general staff, who goads Y. into a song battle. The second line is spoken by Yasmine, Y.’s wife, who tells him, “Let the chief of general staff win.” For me, those two lines are linked to the October 7 attacks. The comprehensive defeat inflicted on the army was one of the main reasons for the revenge that followed. October 7 had not yet taken place, but the state of Israel was not so different. The original screenplay underwent amendments without being completely transformed.I come from a country where life and death are part of daily life. It might be what distinguishes an Israeli director from a French director. An Israeli director can escape neither the state, nor the politics of his country. You can hide all you want but the country will come to find you.

On Y.’s act of war and Israeli art’s position I like the idea that Y.’s act of war toward Gaza boils down to composing a tune. While aviation and artillery bombard Gaza, Y. launches notes of music. Two weeks after October 7, I went back to Israel to try to understand what was going on. I met and listened to a lot of people: friends, acquaintances, rock singers, filmmakers. Everybody, in their own way, was working for the war, with songs and videos. It became the great common cause. Artists were also at war. Art in Israel has chosen its path.

On shooting during wartime

For the first time in my life, numerous technicians refused to work on the film, on the basis of its subject matter, and partly because of me. Every day, another crew member walked off set. I had some very lively discussions with people who explained why they didn’t want to be part of the project. We had to hire a Serbian key makeup artist because we discovered that all the makeup artists in Israel are very patriotic. It occurred to me that I hadn’t changed, but reality had shifted in the country.

Same thing with actors who initially were very keen to be in the movie. Their agents called us to say they had changed their minds with curious explanations. It was shocking. It plunged us into a state close to paranoia. When we were shooting in Cyprus, the war with Lebanon broke out. We had to cut short the shoot. Shooting a film in the middle of a war posed multiple problems for the production team, and increased the cost of the movie.When we were filming within view of Gaza, with the huge plume of black smoke, the soundtrack was full of real-life explosions. When you film a kiss on a hillside overlooking Gaza, you wonder how many people will be dead by the end of the shoot. The father of one of the crew members was a hostage murdered by Hamas. And another told us his soldier son was bombing Gaza. When we shot the scene on the famous “Hill of Love,” on a day when there were a lot of explosions, we went gonzo with a very small crew, because we were in a forbidden military zone. The army intervened and asked us to stop filming. Fortunately, we came across an amenable and interested young officer, who struck up a conversation about cinema with the crew, and gave us permission to shoot for six hours.

(Excerpt from the May 2025 interview with Nadav Lapid.)

Schedule

11/21(Fri)14:45 -

Asahi Hall

11/26(Wed)15:55 -

Human Trust Cinema Yurakucho